Malevich and his Legacy

A Century Later

Can you re-write history? At the same time as history around you re-writes itself forever?

Kazimir Malevich is the artist who managed to create a view on art totally different from how it was perceived until his time, only to end up in obscurity at the end of his life due to a changing world. But even after his death, his legacy lived on in a mythical way, especially orbiting around one single “black square”, a black square we have all the reasons to come back to further down in this article. Now in 2014 the Russian artist is very much in the focus of the attention again: after a very successful and well-attended exhibition at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum at the turn of the year the exhibition moved on to the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn and soon it will go on its final journey of the year, to London’s Tate Modern. This exhibition is a cooperation between the three mentioned institutions, a well-planned and enjoyable show.

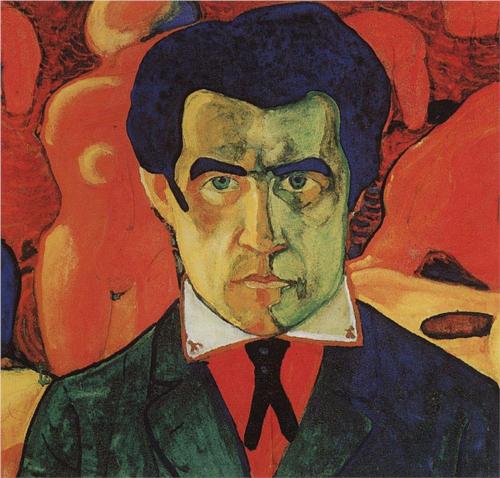

K Malevich – Self Portrait – 1910

A Life of an Excentric

Kazimir Malevich was the first-born son out of 14 children of a sugar-plant manager of Polish decent, born in 1879 just outside Kiev in what is today’s Ukraine. Without any ties to the world of the fine arts or any parental encouragement for pursuing his quest for improving his obvious talent for drawing and painting, Malevich was early on determined to search out his path in life as an artist. While the family kept on moving around throughout his childhood, the young boy early on started studying the handicraft of the peasants in the villages they lived in. After the death of his father in 1904, he successfully enrolled to the ‘Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture’ and in the coming years he quickly became one of the central figures of the Russian art scene.

[ale_one_half]

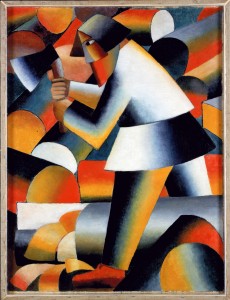

Malevich: The Woodcutter (1912) Courtesy of Stedelijk Museum

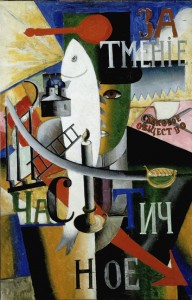

Malevich: An Englishman In Moscow (1914) Courtesy of Stedelijk Museum

During his studies his talent was obvious and studying his early works it’s easy to see a mastery of all the prevalent techniques around in Europe at the turn of the century. His early works were mainly influenced by the impressionists, cubism, symbolism and the fauvist movement. Now in hindsight it’s easy to find clear evidences that his experimentation with the different styles was part of his search for an own identity. Malevich was seemingly also a very vocal part of the Russian art scene with an early influence on his fellow artists. He became an important member of the ‘Donkey’s Tail’ movement in Moscow and the possibly even more influential “Soyuz Molodyozhi” (Union of Youth) in Saint Petersburg. Up until 1917 he was also one of the contributors to the well-known and quite controversial Moscow movement of ‘Jack of Diamonds’.

During the first half of the 1910s the transition from one style to another became almost even more intense, while at the same time his own style turned ever more unique. Together with Mikhail Larionov he sought inspiration from the simplicity of the Russian folk art and they developed the “neo-primitivist movement”, clearly a nod towards the influences he absorbed in his childhood. The shift to new grounds came soon thereafter, when together with his group of artist friends in Moscow they developed the new styles of cubo-futurism – a nod to the angularity of French cubism and the dynamism of the Italian futurism – and a-logism, a collage-like way of painting.

[ale_one_half]

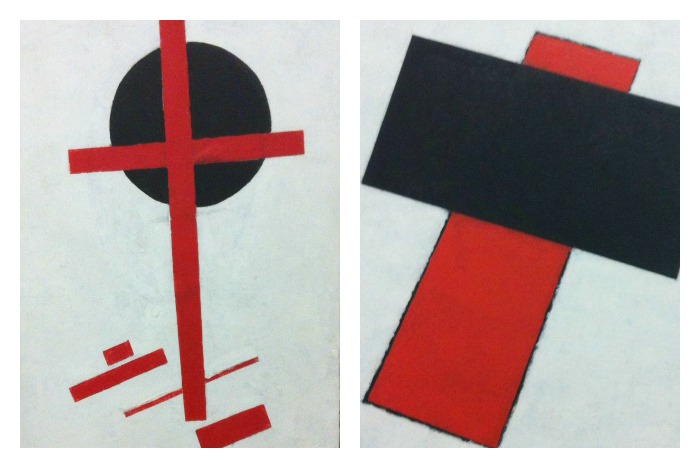

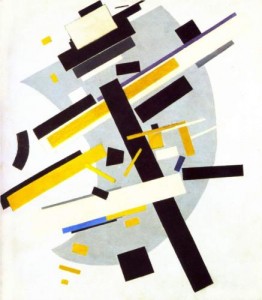

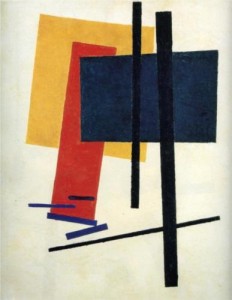

K Malevich – Suprematism – 1916 (Wikiart.org)

K Malevich – Suprematism – 1915 (Wikiart.org)

The years just ahead of the Great War and what later turned into the Russian revolution, Malevich was clearly enjoying his increased influence and during those years his engagement in society was ever increasing. Signs are all there of his stance-taking against the Czarist Russia, especially confirmed by his involvement with the group that in 1913 staged the opera ‘Victory over the Sun’. Malevich designed the scenery and costumes to this futuristic work (Mikhail Matyushin wrote the music and Aleksei Kruchenykh was behind the libretto), the opera in which the People of the Future sets out to capture and destroy the all-powerful Sun – clearly the symbol for Czarist Russia.

Malevich later claimed that while working on the scenography for the opera that his idea about complete abstraction gained stable ground and the years that follow he got totally absorbed in his new project. The works he produced during this year ultimately got exhibited in Moscow in 1915 at the ‘Last Futurist Exhibition 0.10’. During this exhibition Malevich launched his concept of Suprematism, the movement that cemented his name for ever in art history.

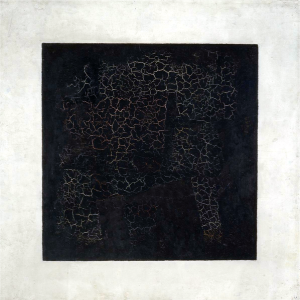

The square is not a subconscious form. It is the creation of intuitive reason. The face of the new art. The square is a living, regal infant. The first step of pure creation in art.

Unusual for the time – and also bold in respect to the expected academic norms of the Czarist Russia – his entire collection was constituting works of abstract-geometric paintings. The centrepiece of this oeuvre was his ‘Black Square’: simply a black square against a white background, painted on a square canvas. What stirred up even more controversy was how he placed this painting in the exhibition, reserving for it the place in the upper corner of the room, the spot always reserved for the religious sacred symbols dictated by the Orthodox Church in every respected Russian home. Malevich’s whole idea to depart from the established standards of art into his “Suprematist” theory was the idea of putting art in the centre without it having any connection with society. Art simply had to exist for the sake of its own, not as the representation of anything real: “art does not need us, and it never did”.

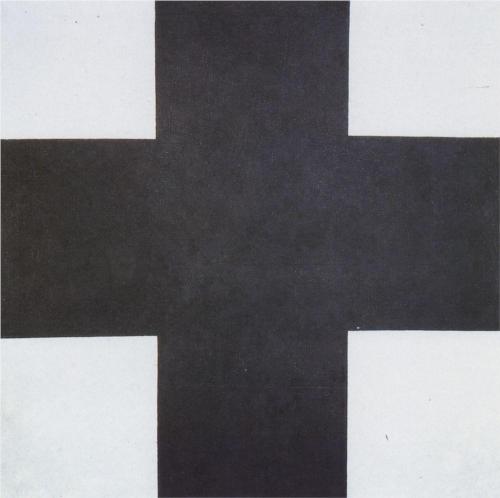

K Malevich – Black Cross – 192 (Wikiart.org)

Malevich was at the top of his world. He clearly reached a status in the Russian art world where whatever he said it was listened to and he quickly gained a large following for his “Suprematism” movement – the name derived from the Latin word “supremus”, meaning “the most perfect”. In the years that followed Malevich extended on his ideas and went ever further away from the norm and into his world of abstractions. ‘Black Square’ was followed by many Suprematist composition like ‘Red Square’, ‘Black Circle’ and – maybe most famously – ‘White on White’, what he considered as the ultimate achievement of his movement. Consequently, soon thereafter in 1919 he declared his experiment as finished.

By “Suprematism” I mean the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling.

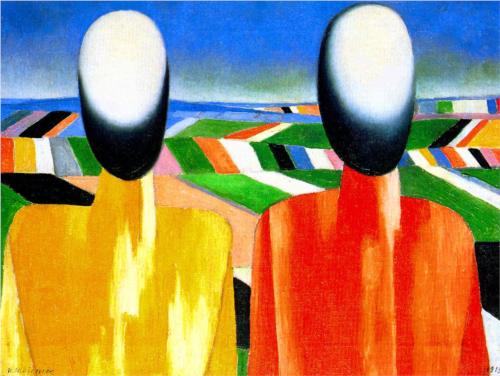

K Malevich – Peasants – 1930 (Wikiart.org)

With the victory of the Bolshevik Revolution, Malevich turned to teaching. His idea that art should be free from serving any special function in society was, however, far from congruent with the ideology of the new Soviet state. Soon enough Malevich became more and more marginalised in the system and eventually coming to a full-frontal collision with it. Malevich, who all his career was focused on killing all linking between art and society, suddenly found himself in a Soviet-communistic system only accepting Social-Realism, an art form only allowed to serve as propaganda for the ‘only-way-forward’. Suddenly, Malevich was seen as the enemy, his theories were considered radical and bourgeois. Like many other of his contemporaries he turned to the rest of the world and embarked on an international exhibition to Germany in 1927, but to the surprise of everybody he suddenly returned to Soviet Russia (although he left a considerable part of his collection abroad).

[ale_one_half]

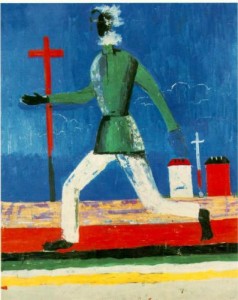

K Malevich – Running Man – 1933 (WikiArt.org)

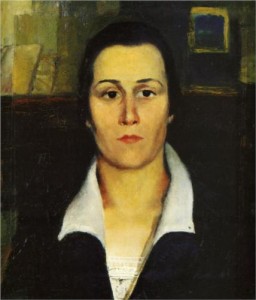

K Malevich – Portrait of a Woman – 1934 (Wikiart.org)

Upon his return his works were confiscated, and he got jailed and banned from making art and possibly as a result of it he soon got sick. When he got freed from jail he spent his final years returning to his peasantry motifs and his new ‘Post-Suprematism’ style was finding his base in his early works. Malevich died of cancer in 1935 and he got buried in secrecy, his role in Stalin’s Soviet was clearly of no importance.

Much of the work that survived is thanks to the collectors George Costakis and Nikolai Khardzhiev, who in all secrecy traced and gathered the artist’s works during the years. Some of the works that Malevich left abroad in 1927 found its way to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, who is in the possession of 24 of his paintings. Many of the works during this year’s exhibitions in Amsterdam, Bonn and London wouldn’t have been possible to see without the efforts of these two men.

FURTHER READING: Art, Supreme Thoughts and Malevich

[ale_toggle title=”‘Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant Garde’ in Bundeskunsthalle Bonn” state=”open”] [ale_tabs][ale_tab title=”Dates”]From Tuesday 11 March 2014 to Sunday 22 June 2014 [/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Opening Hours”]Tuesday and Wednesday: 10 am – 9 pm

Thursday to Sunday (and public holidays): 10 am – 7 pm

Mondays closed (unless it’s a public holiday, then it is open like on a Sunday)[/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Admission”] Still to be confirmed[/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Address”] Bundeskunsthalle

Museumsmeile Bonn

Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 4

53113 Bonn, Germany

Phone: +49 228 9171–200[/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Website”] Bundeskunsthalle Bonn [/ale_tab][/ale_tabs] [/ale_toggle] [ale_toggle title=”‘Malevich Revolutionary of Russian Art’ at Tate Modern in London” state=”open”] [ale_tabs][ale_tab title=”Dates”]From Wednesday 16 July 2014 to Sunday 26 October 2014 [/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Opening Hours”]Sunday to Thursday: 10 am – 6 pm

Friday and Saturday: 10 am to 10 pm[/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Admission”] Still to be confirmed[/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Address”]Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

Phone: +44 (0)20 7887 8888[/ale_tab] [ale_tab title=”Website”] Tate Modern London [/ale_tab][/ale_tabs] [/ale_toggle]