Earth Art – Out To Nature Back To The Gallery

ArtSmart Roundtable: On the Topic of ‘Art Concepts’

The ArtSmart Roundtable is back for October. This month the theme is a broad one: concept in art, conceptual art, a topic with many different possibilities. For us, the choice fell on the concept of Land Art, an art direction that promises a lot and also offers a lot of complexities. Thus, we are heading out into nature, but somehow we will find our ways back into the traditional settings of a museum. For other interpretations of the term ‘concept’, please check out the other posts written by the other ArtSmart members below.

There is a merit of moving art out from the limitation of the four walls offered by museums and galleries. One benefit of it could be to make art available for a broader audience. An audience that would never venture into a gallery or pay the admission fee to a museum. The problem with this “liberating” idea is, though, that quite often the new setting will impose serious limitations on how many people actually will see it. Only because art is out in the open, accessibility often remains a big issue. The concept of land art is an excellent example for this.

Land Art, Its Origin And Its Future

When the Land Art movement – or if you so prefer Earth Art – came through in the late Sixties, one of the guiding principles was to break free from the conventional settings of traditional art and the commercialisation of it. This was the 1960’s after all. It’s all a noble cause, ultimately. In many ways it can be seen as part of the process that we still experience in the efforts to make art accessible for new audiences. The “land art problem” was, though, that very often the projects became overly complicated, often really expensive. It would perhaps be fair to describe them as often overly pretentious, even when measured with the wildest ideas of modern art standards. Thus, it was mostly a movement that seemed to come. There are good reasons though to believe that it could have a revival in our modern times.

There is an aspect of Earth Art that makes it more relevant to our time than ever before. It is in a way an art concept made for the digital age. More often than not most land art projects are best enjoyed from distance. In many cases the only way of really enjoying it is to observe it from an elevation, and in many other cases not even the bird’s eye view is sufficient. A whole multimedia presentation is needed to enable its enjoyment. Therefore, it’s easy to see why our world – where the visual impressions inundate our online feeds – is likely a world better suited for this art form, than it was in its heyday during the 1960s and 1970s.

A Cherry-picked History of Land Art

Land Art is in many ways the human civilisation’s oldest recorded attempts to express itself through art. Several of the mysterious sites we are fascinated by today are large scale projects of which many to this day remain scarcely explained to us modern humans. Just think about the Nazca Lines of Peru or the mystery of Stonehenge. Likely the original purpose of these examples above were different than aesthetic ones. It’s also true that they remain a huge inspiration to many artists in our days. They were early unofficial land art works where humans created visual objects in close congruence with nature.

Nazca lines in Peru.

Formally though, as already mentioned, Land Art had its explosion through the cultural landscape first in the late 1960s. The concept has, however, existed earlier as well, although the actual concept and the term only got used later. The movement – inspired by minimalism and conceptualism – gained in popularity especially in the American hippie-culture when commercialism increasingly became “dirty”, all the while the world – well, a small portion of it – started to care more about environmental challenges. Having these two factors in focus it was no surprise to notice that the art world was soon enough moving out into nature.

The irony of Land Art projects was that, contrary to the goal of de-commercialising art and moving it out of the galleries, they tend to be pretty expensive. “Land artists” in America relied mostly on wealthy patrons and private foundations to fund the works. Not only that, often the main idea behind the projects were to document the process and this required technological expertise, which wasn’t cheap and not that easily accessible. This latter would surely be a lesser challenge today in our smart-phone era.

Money, or rather the lack of it, was at the end also the factor contributing to the decline in popularity of land art projects. With the sudden economic downturn of 1973 the funds dried up and the hype around land art slowly diminished. Some notable exceptions carried on, artists whose legacy even today is significant.

The Major Names and Works in Land Art

Robert Smithson

It could be said that any summary of land art should start and end with Robert Smithson (1938 – 1973).

His large-scale projects employed natural elements like earth and rocks to construct art works that both manipulated and preserved the natural landscape.

His most famous work, to this day widely regarded as the centrepiece of the land art movement is Spiral Jetty. Spiral jetty is a work constructed on the northern shore of the Grand Salt lake in Utah. It’s a 1,500-foot-long (460 m), 15-foot-wide (4.6 m) counterclockwise coil stretching out into the lake. After snow-rich winters in the neighbouring mountains, when water level is rising, the work is occasionally totally covered by water. The artist also documented the construction of the sculpture in a 32-minute color film, also titled Spiral Jetty. Some even considered this film the main work of Smithson’s instead of the jetty itself. The movie is a work to this day often used as a centre-piece of many land art exhibitions – as you will see below.

Spiral Jetty – Robert Smithson

Walter De Maria

Another big name in the field was one of our universally personal favourites in the art world: the legendary Walter De Maria (1935 – 2013).

The multi-talented Berkeley-born artist who broke through in the New York art scene of the Sixties, also happened to be the early drummer of the band The Velvet Underground.

De Maria, famous for his sculptures, became later one of the major names of the land art concept and continued with land art projects long after the general decline of the genre.

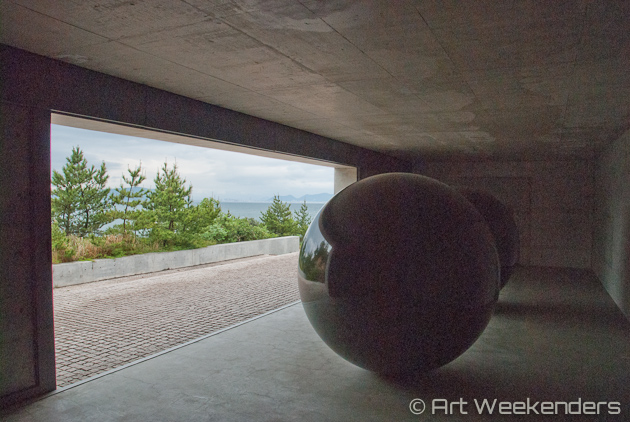

The American artist became especially popular outside the United States, and then particularly in Japan (as witnessed by the fantastic Naoshima Art Island we covered earlier) and in Germany, where one of his most famous works can be found, his mystical Vertical Earth Kilometre found in Kassel. This is possibly the biggest work of art in the world that you can barely see…: being a one kilometre long brass-rod, five centimetres (two inches) in diameter drilled straight into the ground of the Friedrichsplatz Park. In reality all you can see of it is its circular top, framed by a two-meter square plate of red sandstone, while the rest is left for your own imagination.

Andy Goldsworthy

Further names in the field worth keeping an extra eye out for are the British Andy Goldsworthy (born 1956), with works more easily appreciated by the general public. His land art often can be found in some of the best sculpture parks around the world (check out our sculpture park post for some inspiration), in Goldsworthy’s case with the Yorkshire Sculpture Park as the main destination of pilgrimage.

Andy Goldsworthy – Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Land Art in Our Days

As the example of the contemporary artist Goldsworthy shows, there is a currently active land art scene in existence as well. In many ways land art is, some fifty years after its initial heydays, more relevant than ever. Given that land art is often difficult to reach, due to the “earthly challenges” it faces, our multimedia world and social media tainted world definitely creates forums for expanding its potential reach. Combine this with a strengthening environmental movement, triggered by global warming and inspired by for instance Naomi Klein’s ‘This Changes Everything’ and you could have a fertile ground for land art projects.

Seen/Unseen Known/Unknown, artist Walter De Maria – Naoshima, Japan

If you think about it, land art is really made for a specific place and the thought of being able to transport it to another location is just daunting. The documentations of this kind of projects have, therefore, often taken an even more central role than the actual work of art. A good example of this is for instance Robert Smithston’s Spiral Jetty presented above.

But land art has also made an entrance into the exhibition world as well; almost ironic when knowing that its main appeal from the beginning was to move out of the restrictions of the walls. There have been large-scale exhibitions just recently in Los Angeles and a few in Europe. In fact, a land art exhibition was organized some years ago a short ride from our home.

Land Art Exhibition in The Netherlands: Kunsthal Kade in Amersfoort

During the fall of 2015 Amersfoort’s Kunsthal Kade introduced the Dutch audience for the first time ever to what the earth art concept really means. The documentary movie of the Spiral Jetty, introduced above, was one of the main works presented for the Dutch public. ‘Exhibition Land Art’ aimed to connect the earlier ‘land art’ artists with the contemporary ones. As a result the main emphasis in the show was on six of the main land artists from the early days of the genre (Nancy Holt, Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, James Turrell, Richard Long and Marinus Boezem) and their influence on a younger generation (Francis Alÿs, Tacita Dean, Mario Garcia Torres, Zeger Reyers, Pierre Bismuth and Lara Almarcegui). The exhibition’s interesting merit was that it showed how much today’s artists owe to the pioneering land artists of the past.

Reflecting further over it, the whole concept of Land Art, Earth Art, Earthwork, is an interesting concept, where the drive that took the artists out from the galleries in an exhibition like this one comes back behind the four walls. There is an intriguing part of it that feels like worth exploring further.

The ArtSmart Roundtable is an initiative of different art-interested travel bloggers from around the world. Once a month the members contribute with an article on the same theme, which this month was the broad idea of concept in art. Please check out the other articles in this month’s round of articles as per below.

Daydream Tourist: Changing Paintings After They are “Finished”

This Is My Happiness: Northern California’s Greatest Artist: Wayne Thiebaud

The Wanderfull Traveller: The Conceptual Design of Vancouver’s New Art Gallery

ArtTrav: Nurture and Hospitality at Santa Maria della Scala, Siena

WanderArti: The Concept of Travel in Art Through the Ages