Art Against the Established Norms

The French Impressionists Challenge of The Salon

A David and Goliath Art-Tale

This article is our first contribution to the ArtSmart Roundtable, a monthly event of a group of art-focused travel bloggers who generously welcomed us to their community. We’re extremely happy and thankful for this opportunity and we’re looking forward to the monthly contributions ahead of us. The theme for the month of February is Contrast – a topic that at first glance opens up for many possibilities, but which also offers plenty of challenges. Our aim with this article is to tie the most recent book of Malcolm Gladwell’s back to the birth of the French impressionist movement, via their widely contrasting style to the accepted standards of their era, dictated by the ‘Salon’.

How do you break through the established norms? Can you create a forum for yourself if the conventions of the days are favouring values, styles and norms totally different from your own? It’s a question that often comes up in our lives and in society at large, and often it’s only in hindsight that the reasoning behind it can be understood. That’s regularly the case in the art world too, around the emergence of any new style, as has been the case for instance with the Impressionists in the second half of the 19th century.

Malcolm Gladwell, the successful writer of “Blink” and “The Tipping Point”, is tackling the issues of why underdogs succeed better than their situation first gives reason to believe in his latest book David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants

. The French Impressionists play a quite important role in his explanation of this allegory: why it’s better to be a big fish in a little pond, instead of being a little fish in a big pond. Simply put, it’s easier to succeed if you create an environment for yourself where you feel more comfortable and more at ease with your surroundings, than if you have to perform under highly competitive circumstances where you difficultly get noticed.

It’s very easy to see the logic Gladwell uses, while at the same time it’s also quite easy to see why others criticise the writer for his over-simplified reasoning in support of his theories. The fact remains, Gladwell definitely is a master of bringing a topic to life and getting the world curious for the ideas he brings to the table. Exactly that’s what happened to us when it comes to his thoughts around the birth of the Impressionist movement.

Back some one and half century ago, Paris was the centre of the world, everything that was culturally important and credible had to be considered accepted in the French capital. In the Paris of the 1860’s the Académie des Beaux-Arts had an almost all-encompassing power over the happenings of the era and their annual art show, the Salon de Paris, was the event where the golden standard of the day was decided. The objective of the Académie was to preserve the traditions of French painting standards, and anything that fell out of the norm was doomed to the peripheries of existence. The themes and motifs of the day valued historical subjects, religious themes and portraits, while landscapes, still life and images from the everyday life were considered banal. Abstract work was unheard of, everything needed to be realistic-looking, while clear traces of paintbrushes were considered unacceptable. Most importantly, in general the space for individual expressions were suppressed.

Edouard Dantan – ‘Un Coin du Salon en 1880’

All the above are characteristics that a group of artists who regularly met up in the ‘Café Guerbois’ in the neighbourhood of Batignoles didn’t share, or had difficulties adapting to. Just like many other artists of the time they struggled getting accepted to the Salon, and at the few occasions any of them got any works in, they were close to being ridiculed.

The norm for the annual selection to the Salon followed the same pattern each year: by the first of April all works had to be submitted to the jury and if the paintings got accepted by the very critical members, the works would be exhibited at the Palais de l’Industrie, the site of the purpose-built exhibition hall between the Champs Elysée and the Seine. The accepted paintings were hung together with thousands of other works, covering walls from floor to ceiling, for a six weeks period beginning in early May.

The Salon each year was attended by a million people, who somehow all tried to catch a glimpse of the works in the midst of the tumult. The works that gained the favour of the jury got medals and their values soared on the art market. On the other hand, those who didn’t make it to the Salon could almost impossibly even sell their work, not to mention get a good price for it. As it happened, all rejections at the Salon got a red letter “R” painted on them. One year – in 1863 to be precise – Emperor Napoléon III somehow got the impulse that the R-lettered works should be judged by the public and hence the first ever ‘Salon des Refusés‘ – ‘The Salon of the Refused‘ was organised. While many went to this event just for the laugh, it still turned into a great success, where attendance numbers were rumoured to be higher then the actual Salon‘s.

Edouard Manet – Luncheon on the Grass (1863)

One of the rejected works was Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass, which was refused because the image of a picnicking nude with two dressed gentlemen was deemed unacceptable. While nudity was the norm in historic and mythological motifs, clearly, if the depiction was related to the real life it was met by different standards. Manet’s piece made it to ‘The Salon of the Refused‘, and thereby in any case achieved something: it opened up the public’s eyes for a different art than what they usually saw at the Salon.

Edouard Manet – Olympia (1865)

Two years later, Manet finally got accepted to the “real” Salon: his Olympia depicting a nude prostitute created again some public outcry, but unsurprisingly no prizes. For Manet during his entire career the Salon remained his holy grail, for him making it there was the only way that could be counted as being successful. The other painters in the group that carried on regularly meeting at the ‘Café Guerbois’ started in any case to consider a different approach: being totally dependent on the Salon became a burden and they started toying with the option of opening their own exhibition instead.

In 1874 this finally happened when 165 works by Cézanne, Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley were exhibited in a totally different way than what the Salon prescribed: most importantly, the paintings exhibited were hung in such a way that they could clearly be seen by the public, and without the obstructing crowds. The month-long event turned into a smaller success with some 3,500 vsitors. There was, however, one artist’s work totally absent from here: Manet – who often been considered the leader of the group – was not participating.

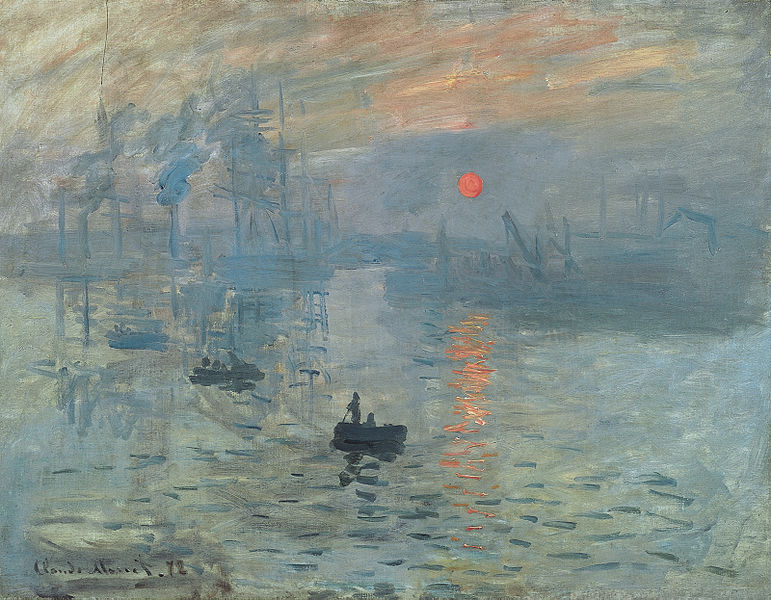

Claude Monet – Impression, Soleil Levant (1872)

Despite the negative criticism from some experts – someone for instance said that the paintings were like “loading a pistol with paint and firing at the canvas” -, the exhibition got critical praise as well. Thanks to that, the Impressionists exhibition was repeated seven more times in the years that followed (although it was only Pissarro who participated in all of them). The differences in the opinion between the artists differed and the Salon to most of them still remained the golden standard for success.

Still, these initiatives were enough to trigger a new way of looking at art and suddenly it wasn’t only what the Salon dictated that could be considered as good. While first the public almost ridiculed the work of the Impressionists, slowly times changed. Even the name “impressionist’ was coined almost out of ridicule, when a critic named Louis Leroy referred to Monet‘s ‘Impression, Soleil Levant‘ (Impression, Sunrise) as at most a sketch, hardly to be considered a finished work. The name, however stuck with the group, which actually had, despite the negative clang to it first, no objections to it.

With the passing of time not only the world of the Impressionists changed and gained ever more acceptance, but predictably, the power of the Salon slowly faded as well and by 1890 the once all powerful institution imploded under its own weight.

If we fast forward to today’s world, this kind of conflicts in the world of art is – at least on the surface – harder to find; we tend to believe that there’s space for everyone in today’s art life and all kind of artistic expressions are welcomed. Artists like Ai Weiwei, Damian Hirst, Jeff Koons and many more strive in fact on precisely that: at being controversial, going against the norm. But does that mean that there are no established conventions to fight against for an artist from today? Likely the obstacles are all there now as well, but what the forces that drive success today are, will likely only be understood in hindsight.

And that’s also why Gladwell‘s explanation can likely be criticised. He tends to oversimplify the case with the group of French painters. The Impressionists indeed tried to break out, but not because they rejected the Salon, more because they had no choice if they wanted to be seen. Therefore, it can’t really be seen as if they managed to break free from their days’ standards, their future success is more likely due to the fact that times in general changed.

With time everything that is established will trigger a contrasting view, life and nature just work like that. But not every contrast of styles will lead to a success story like the Impressionists’s one.

The articles in this February round of the ArtSmart Roundtable can be found here:

- Christina of Daydream Tourist – Pablo Picasso: Creative Chameleon

- Jeff of EuroTravelogue – Danube River Cruise – A Contrast in Scenery, Architecture and Time

- Erin of A Sense of Place – What’s With The Wall Colors?

The ArtSmart Roundtable also has a group on Facebook for art and art-related travel news; join us for more articles like the above.