Do Folklore and Folk Art Have a Place in Modern Society?

A new month and a new round of the ArtSmart Roundtable are here. This month’s theme is a topic familiar for all of us, but at times still hard to know how we connect to: folklore and folk art. It’s a very broad area, often hard to define and nail down and regularly taking different shapes depending on where you are. It’s also a field which stretches to every possible corner of the world, and where the quality is diverse and varying. But what is the role it has in today’s society? Is it slowly disappearing from many regions without us noticing, or is there a way for it to embrace our contemporary world? Questions which we will go into in more details below. Besides our contribution don’t forget to check out the other articles written for this month’s ArtSmart Roundtable, found at the end of this article.

In our modern times, despite our differences and varied opinions, we are coming increasingly closer to each other, as a result of globalisation and the spread of popular media and culture via the Internet. Our worlds are getting more interlinked, international, and the individualistic expressions through fashion and design are becoming boundary-less, where national identities are increasingly vanishing. It hasn’t always been like this; in many parts of the world folklore and folk art had a dominant role, where local symbolism expressed your identity and defined who you are.

Today it’s fair to say that we see less and less of this phenomenon, especially in the West, but not only. Thereby, the question is justified: is there really space for folklore and folk art in our modern, homogenising societies? If so, where can we find it, and is it maintaining its old form, or is there an expressionistic evolution taking place? Is there a modern version of folk art around us?

In contrast to fine art, folk art is primarily utilitarian and decorative rather than purely aesthetic.

A Personal Relationship to Folk Art

During my childhood folk art always had a substantial role in my life. Like everyone with roots in Eastern Europe will testify, folklore is to this day still a big part of life there, as it has been for many generations. Folk art and national identity are very closely linked in that part of the world and, throughout my Hungarian upbringing, Hungarian handicraft was part of everyday life. Be it in form of tablecloths, pottery, or decorative artifacts, it was always there. I’m grown up in Transylvania, Romania, and for a minority people like us Hungarians in that region, it carries an extra symbolic value. All around the country, though, different regions strongly identify with their local style, indifferently of the language they speak. In a way, folklore keeps people with one foot steadily anchored in the past, establishing the sense of being part of something bigger.

Later on, in my youth, life took me to Sweden, where – maybe surprisingly to many – folklore traditions always had a strong role, especially in certain central regions of the country like Dalarna. It is, however, fair to say that modernisation transformed these traditions considerably and while folklore has a small role in day-to-day life, today a certain type of symbolism from folk art got transferred into a contemporary era. How exactly? We’ll see a bit more of it further down, but a hint is design.

This symbolism is even more prevalent in the country where my heart found a home in the more recent years of my life, here in The Netherlands. Clogs and tulips anyone? I’m sure you’ve heard about them somewhere… And yes, they certainly have an important role in Dutch traditional folklore, but also in the modern era. And there’s more.

A Changing World, Maintained Identity

Throughout the years, the two of us behind this site have been travelling quite a lot, as “art weekenders” but also on the trails less travelled, for instance through South America and more recently in West Africa. As observers on the road, there are two ways of studying our surroundings (just to simplify life a little bit): by looking for the familiar, and by finding the uniqueness in a place. While it’s true to say that all so often we find ourselves in familiar territory – where jeans, t-shirts, glaring music and loud TV-shows in the background serve as connectors, even in deep Amazonia – the true identifiers of a place are always there, details that put the location and its people aside from others.

Facts that make a place unique. Quite often these details are deeply rooted in the folklore and in most cases expressed in folk art and craft, often passed down through generations, carrying a deeply rooted regional or even national identity with them. A sense of belonging. In most cases folk art feels very regional and outside its local context it just feels “wrong”. In some other cases the local folk art feels timeless, even boundaryless. It just transcends all cultural restrictions.

When is this transcendence happening, and what is the psychology behind it? Is there a place for folk art in modern society and when does it “work”? During travels, and at times in retrospect, these are questions we often wondered about.

Let’s have a look at a few examples from our own experiences and observations to help with our analysis.

Andean Art and Its Influence on Fashion

Folklore at Los Uros, Lake Titicaca

While travelling through South America local traditions are joining you around, especially if you follow the Andean trails. Be it in the Salta region of Argentina or around Otavalo in Ecuador, the distinct Inca patterns are everywhere. A lot of the fascination westerners have with the local merchandise is attributable to the world-famous alpaca wool, but just as much to the famous patterns. Sure, in its current form it’s mostly appealing for practical purchases to keep you warm (sweaters, hats, scarves). However, more and more of it finds its way into the finer fashion salons of the booming cities of the Andean nations. Peru is possibly the country where this trend is most obvious: there are many up and coming brands taking advantage of the Inca heritage, and likely none of them does it better than the fashion house of Kuna. Sure enough, the emphasis is certainly on the material, but the Andean Influence is traceable in the designs as well, albeit definitely put into a westernised context.

Kuna – Peru’s flagship fashion brand using alpaca and vicuna wool for their designed products (kuna.com.pe)

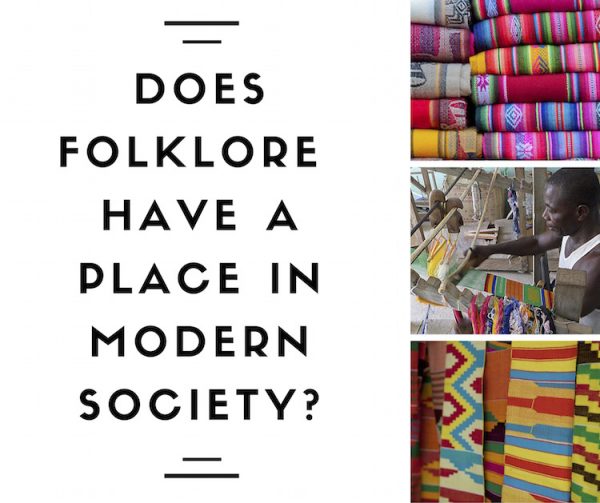

West African Kente – From the Ashanti to World Fashion

Kente weaving in Kpalime, Togo.

One of the brightest stars on the West African cultural folk heritage sky is the kente weaving technique, perfected by the Ashanti over the past centuries. The Ashantis, one of the most successful tribes or nations ever on the African continent, are of course even more famous for their gold, but the kente – originally silk-based – textiles produced in today’s Ghana and neighbouring countries are highly attractive further and further afield. One strongly contributing factor is the Dutch fashion house Vlisco, which is largely building its huge success on batik fabrics since 1846, bringing Indonesian folklore not only to Africa but also to European fashion houses through designers like Vlisco Atelier and Victor & Rolf.

Vlisco dresses for a new summer season. (vlisco.com)

Delft Blue from Granny’s Teapots to Trendy Home Decoration

To stay close to home, here in The Netherlands, besides cheese, clogs and tulips another strong “Dutch identifier” is the famous blue and white Delft Pottery, aka Delftware. While maybe it’s debatable if it fully qualifies as folk art – it was after all developed by commercial-minded artisans fully influenced by Chinese traditions – there’s no denying that it always had a very strong popular anchoring in Dutch society ever since the 17th century. For a long while though, especially in recent decades, Delft Blue became more and more a symbol linked to older generations and tacky(ish) souvenir shops. Recently, however, it ended up being part of a collection developed by no one less than Marcel Wanders, the most famous of Dutch designers, who is possibly Dutch coolness personified.

Marcel Wanders designed objects from MOOOI’s Delft Blue Collection (moooi.com)

Swedish Dala Horses – from IKEA to Everywhere

Sweden is a country where folklore traditions have always been very strong, be it through music, outfits or decoration in general. While today the traditions are fading more and more (I wonder how many Swedes still could even figure out how to dance a Swedish polka), in certain other respects the folk art symbols are stronger then ever. For instance, many of the famous glass manufacturers like Kosta Boda and Orrefors use traditional motifs and techniques in their designs of the world famous goods they distribute worldwide. But nowhere else is the symbolism as strong as with the little wooden horses – Dalahästar – you’ll find everywhere in Swedish design these days, starting with IKEA, becoming a beloved and respected symbol for the whole nation.

The Swedish Dalecarlian horse

Hungarian Embroideries – The Exception Against the Rule

As Hungarian-born, traditional embroideries have of course always been a part of my life. To this day, I find them beautiful, well-made and I feel a certain level of pride for it. Even today the tablecloths, blouses and cushions play an essential role in Hungarian day-to-day life. However, what I don’t seem to find evidence for is renewal, ways of embracing the modern world. While I see the appeal for the goods, in most cases I have difficulties seeing it conquering the world significantly outside the country’s borders with one or two feet steadily left in the past. Maybe it’s a Hungarian treat. These days renewal is not a big thing in the country, where instead of openness suspicion against the world around is ever bigger. Maybe no wonder for a small nation surrounded by foreign tongues for centuries, but still; ever since the migration started more than thousand years ago somewhere in Asia, it is part of the local survival mechanism (but that’s a topic for another blog).

Asian Timelessness

While we’re looking eastwards, let’s head further towards Asia. It’s no surprise by now that Asian art and craft grown out from local folklore have had a strong appeal on the Western world already for centuries. From Turkey to India, from Persia to Vietnam, and of course the giants of China and Japan, all have strong folk art traditions that easily transcend borders and cultures. This appeal of oriental art and craft on other societies is obvious, but maybe nowhere is it as much influencing modern, local life as in Japan. Be it interior decoration, clothing (kimonos anyone?) or just the quintessential Japanese way of being are all very deeply rooted in Japanese folklore.

Dressed up for a ceremony in Miyajima, Japan.

What makes folk art time- and boundaryless?

Through the above virtual tour from one corner of the world to another it is obvious that folk art is everywhere, even if often we just don’t even seem to notice it. Despite the fact that our world is becoming more homogeneous, it is clear that local traditions prevail, in some regions more strongly than others. Some of it has a tendency to stay timeless. Some of the folk art from around the world seems to have a broad appeal further afield as well. The boundlessness of Asian heritage, kente weaving or Andean patterns can easily appeal to culturally very different people. What can it be? Is it thanks to the simple geometric symmetry they offer? The subtle colours and patterns? I would say yes.

Andean textiles

On the opposite end there’s a lot of local folk art that slowly fades away or that unlikely will get a broader international appeal. This is certainly a problem in Europe, where many regions have only remnants of their folkloric heritage left, even in culturally strong countries like Italy. In Eastern Europe – where flowers, wild patterns often dominate – the likelihood for folk art to remain stronger is so far good, but it is also likely that it will remain mainly locally anchored. Some traditions are simply best where they are based? Or who knows, change might be just around the corner thanks to a new generation of young local designers.

How do you look at folk art and folklore? Do you agree with us that there’s a place for it in our modern societies too and can even evolve into “bigger phenomena”? Do you think there is a risk that the modern soon eradicates all traces of the folksy? Should we do something about this before it’s too late? We’d be happy to hear your views!

Other folklore-inpired stories in this summery month from the ArtSmart Group are as follows:

This Is My Happiness: Folklore and the Intersection of Art and Culture written by Jenna

Daydream Tourist: Digging into the Legend of Troy written by Christina